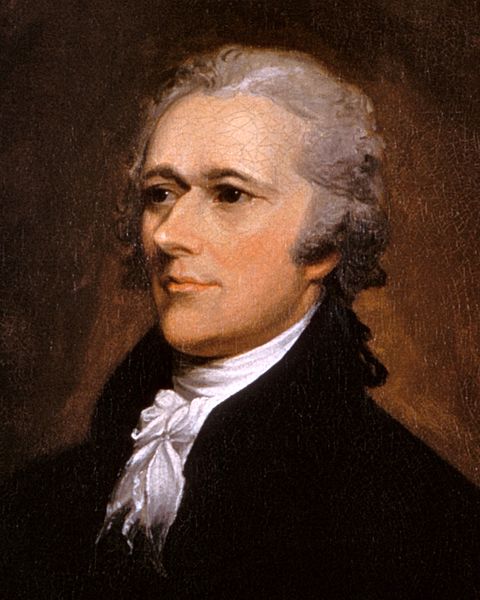

(John Trumbull’s 1806 Painting – Source: Wikipedia)

(John Trumbull’s 1806 Painting – Source: Wikipedia)

Paul Johnson wrote that “[Alexander] Hamilton was a genius – the only one of the Founding Fathers fully entitled to that accolade.” Reading Ron Chernow’s splendid biography of the man, Alexander Hamilton, you quickly realize why Johnson endowed him with such praise.

Through hard work and an early self-learning (and much good timing), Hamilton made his way from the utter obscurity of his early life in the Caribbean island of Nevis to an elite education at what is now Columbia University in New York City. Serving as a captain in an artillery company at the outset of the Revolutionary War, he quickly made his way to George Washington’s staff. At the age of 23, he effectively served as Washington’s Chief-of-Staff, drafting his letters and oftentimes making proxy strategic decisions in Washington’s absence. From there Hamilton played a key role in the Constitutional Convention and was the chief author of the Federalist, alongside James Madison and John Jay, writing 51 of the 85 essays promoting what would become the U.S. Constitution. And from there, at the age of 34, he served as the first Secretary of Treasury, forming a national bank to develop credit and create cohesiveness for the weak fledgling nation. While Hamilton wasn’t there in Philadelphia arguing for independence at the First and Second Continental Congresses prior to the War, he was however a key, if not the key, architect in the creation of the structure and foundation of the apparatus of the American government.

But if Hamilton was indeed the only Founding Father deserving of the title of a genius, why wasn’t he ever seriously considered for the top spot of president (in the 1796, 1800, or 1804 elections before his duel with Aaron Burr)? In other words, despite his vast intelligence and substantial achievements, why wasn’t Hamilton viewed for the top leadership spot in the country?

Answering this question, Chernow writes:

Though blessed with a great executive mind and a consummate policy maker, Hamilton could never master the smooth restraint of a mature politician. His conception of leadership was noble but limiting: the true statesman defied the wishes of the people, if necessary, and shook them from wishful thinking and complacency. Hamilton lived in a world of moral absolutes and was not especially prone to compromise or consensus building. Where Washington and Jeffferson had a gift for voicing the hopes of ordinary people, Hamilton had no special interest in echoing popular preferences. Much too avowedly elitist to become president, he lacked what Woodrow Wilson defined as the essential ingredient for political leadership: ‘profound sympathy with those whom he leads – a sympathy which is insight – an insight which is of the heart rather than of the intellect.’ Alexander Hamilton enjoyed no such bond with the American people. This may have been why Madison was so adamant that ‘Hamilton never could have got in’ as president.

In short, Hamilton was a very good manager, an effective administrator, and a farsighted planner, but not a great leader. He was highly effective at identifying a problem, proposing a solution, and implementing it. He could skillfully standup and harness the mechanisms of bureaucracy, such as a tax revenue system. And his conception of the future of the United States demonstrated incredible foresight and realism. In other words, he was excellent at ‘getting things done’. But on the other hand, he lacked empathy with ordinary people, which is such a crucial component of leadership. (This is not to mention the numerous enemies he had throughout his rise and fall from power.) One imagines a modern Hamilton being a great White House Chief-of-Staff, National Security Adviser, or, of course, Secretary of Treasury – someone who deals with long-term strategy for an administration or fixes large-scale problems – but definitely not President.

Empathy – the ability to put yourself in another person’s shoes – is one of the key characteristics of an exceptional leader. Philosopher Isaiah Berlin explains, in the wonderful essay “Political Judgment”, that empathy in politics “is semi-instinctive knowledge of these lower depths, knowledge of the intricate connections between the upper surface and other, remoter layers of social or individual life… that is an indispensable ingredient of good political judgment.” Hamilton lost that connection between the top echelon of American politics and everyday American citizens.

It is a curious irony that Hamilton, “the bastard brat of a Scotch pedlar” as John Adams would call him, who grew up in such harsh and unfavorable conditions, and who can be arguably called the only true genius of the Founding Fathers, would become so disconnected to the feelings of everyday people.

Comments on this entry are closed.