I recently finished David Herbert Donald’s excellent one-volume book on Abraham Lincoln. I read it while researching for my thesis, but felt compelled to re-read it. When you read a book for pleasure, as opposed for research, especially under a very tight deadline, you’re left with a very different lasting impression. Your objective in reading the book changes; you can take your time and simmer on some of the deeper and more subtle issues the book presents. This time around I’ve learned a great deal more about Lincoln’s background and personality, his thought processes, and his nuanced leadership style. One thing I learned in particular was the way he managed the doubts, apprehensions, and hesitations of his generals.

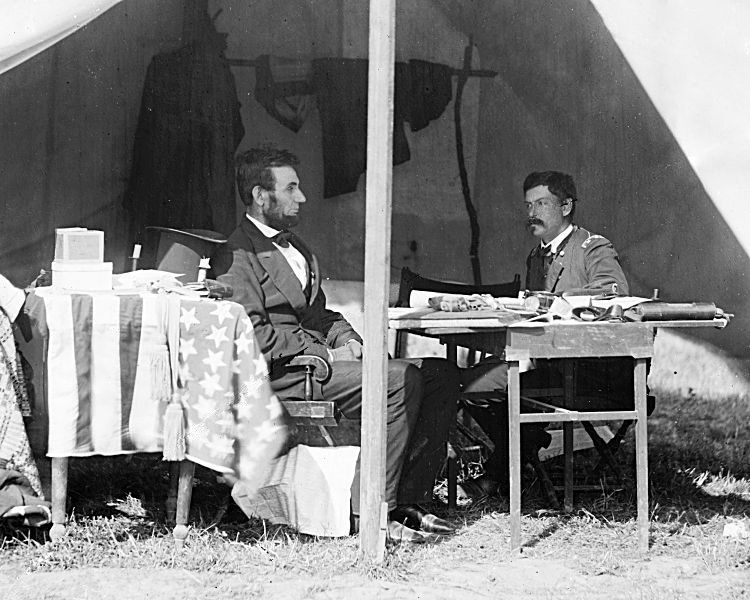

(Lincoln and McClellan in McClellan’s tent. Source: Wikipedia)

(Lincoln and McClellan in McClellan’s tent. Source: Wikipedia)

One of Lincoln’s first generals-in-chief of the entire Union Army was a young prodigy named George McClellan. McClellan’s credentials were indeed impeccable. Born into a wealthy and prominent Philadelphia family, he attended the University of Pennsylvania at the age of 13 before transferring to the United States Military Academy at West Point, graduating second in his class. He was a decorated veteran of the Mexican-American War and served as a top executive for two railroads, all just over the age of 30. As he was selected to lead the Army, the press was lionizing him as “the young Napoleon” and “something of ‘a man of destiny’”.

But once he got into the field and settled into his new role, McClellan had a tendency to find any excuse to delay action. The ambitious and wholly unrealistic initial plan he handed to Lincoln called for at least 500,000 trained soldiers, which was more than double the number they currently had. That meant that it would take at least six and probably more like eight months to get the new troops recruited, organized, trained, and fully supplied. This long delay was something Lincoln was simply unwilling to accept.

Although the Confederate Army was camped dangerously close to Washington, DC, McClellan was very hesitant to engage them. He believed that the “enemy have 3 or 4 times my force”, summing to what he believed to be 150,000 men. He was desperately concerned that his army would be torn to shreds if he engaged them in battle, and that it would be wise to wait until his army was greatly reinforced with more volunteers. However, in actuality, the Confederate Army that he was facing consisted of less than 40,000 men. Throughout his entire time in command of the Union Army, McClellan constantly overestimated the enemy’s forces.

In reaction to Lincoln’s constant inquiries, stemming from his growing impatience, McClellan testily stopped telling his plans to anyone in the War Cabinet, let alone his own military staff. Lincoln, recognizing own his limited military knowledge, allowed this to go on for some months. And then once the Congressional Joint Committee on the Conduct of the War, created in response to growing dissatisfaction with the direction of the war, demanded to know his plans, McClellan fell sick with typhoid fever and missed its critical meeting, sending proxies in his place. In front of the committee his proxies were befuddled, claiming that not even they knew of his plans.

It seemed as though McClellan came up with every excuse in the book to abstain from fighting. And as Donald aptly summarized it, “At the heart of the problems [of the dissatisfaction with Lincoln and the conduct of the war] was the failure of the armies to advance and win victories.” It took a little while, but Lincoln recognized that his belief that the destruction of the Confederate Army was the object of the Union Army (as opposed to the capture of the Confederate capital of Richmond) was incompatible with McClellan’s caution and inaction. Lincoln dismissed him as general-in-chief of the Union Army and then later dismissed him as commander of the Army of the Potomac after his failure to follow-up his victory after the Battle of Antietam. After going through several more generals, Lincoln eventually found a winning duo in Ulysses S. Grant and William T. Sherman, whose boldness and momentum were antithetical to McClellan. In fact, Lincoln brushed aside protests against Grant (his drinking problem and lax discipline alarmed many people), commenting, “I can’t spare this man; he fights.”

As James McPherson wrote in his short book on Lincoln’s wartime leadership, “Having known nothing but success in his meteoric career, McClellan came to Washington as the Young Napoleon destined by God to save the country. These high expectations paralyzed him. Failure was unthinkable. Never having experienced failure, he feared the unknown.”

At the root of McClellan’s timidity and inaction was his fear of failure. This fear was built upon his tremendous uninterrupted success as a young man. But his fears were greatly inflated by the press’s sudden and widespread trumpeting of his achievements, which created a great sense of hope among those in North. Such praises and expectations – which he certainly did not discourage – made McClellan extremely cautious from the outset of his command. And as a very ambitious man, he did not want to lose the public’s favor by losing grave battles. Not only would his reputation be tarnished – irreparably in his mind – but he would have to face the fact that he was vulnerable and human like anyone else.

One of the lessons that I derived from re-reading Donald’s book was that what often holds us back from doing any sort of big undertaking that has the potential to change our lives – whether writing a book, starting a business, going back to school, leaving a cozy job that we hate – is the fear of failure. And that this fear is manifested through endless excuses: “If only I could read one more book to prepare for my research.” “If only I could save $10,000 more dollars for startup capital” “I’ll apply for grad school once I’m settled.” Blah blah blah.

After re-reading this book, I have come to recognize that I used to have this illusion that there is this moment in time when I will be fully prepared for whatever undertaking I wish to do. Just as General McClellan thought that once he had twice as many trained and equipped soldiers, he would finally be fully prepared to defeat the South. But that is false. In fact, it is just an excuse to prolong the time when you need to put the wheels in motion and begin the hard work necessary to accomplish your goal.

Undertaking a new project, job, or life changing endeavor is scary. You’re not sure what it will take or if you’re even qualified. But if you force yourself to action before you feel fully prepared, learn as you go, and see your failures as opportunities for reflection and improvement – and trust me, there will be plenty of these opportunities – you will be much closer to reaching your goal than if you waited for that illusory day when you’re finally fully prepared.

Comments on this entry are closed.