When John Adams was just about to be inaugurated as the second President of the United States of America, he had tremendous shoes to fill from George Washington. Not only that, the government was still very much in its infant stages and was highly vulnerable to destabilizing internal and external forces.

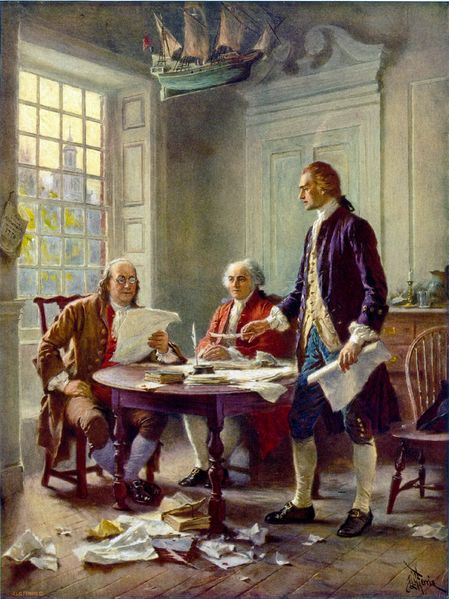

(Writing the Declaration of Independence by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris c. 1900. Source: Wikipedia)

(Writing the Declaration of Independence by Jean Leon Gerome Ferris c. 1900. Source: Wikipedia)

He and his vice president-elect, Thomas Jefferson, recently had a cooling of their relationship, which was one of the most remarkable in world history. As the so-called tongue and the pen of the Revolution, respectively, Adams and Jefferson were among the very most influential men at the Second Continental Congress, which finally declared independence for the American Colonies. While Jefferson is rightfully known as the key author of the Declaration of Independence, it was Adams who nominated and persuaded his and Jefferson’s fellow members on the Committee of Five to accept Jefferson in this role. It was here where their long and profound relationship blossomed, while eventually strengthening in the mid-1780s when they were both part of a foreign mission in France.

But as they were both invited into the cabinet of George Washington, Adams as Vice President and Jefferson as Secretary of State, their personal relationship began changing. The debate of the role of the federal government, particularly the role of the president and the executive branch, and of foreign policy during the French Revolution created a fundamental rift in their outlook. Not only did it become apparent that their worldviews had changed, but their views toward each other began to change as well.

The political union that was necessary to unanimously declare independence was immediately fractured after victory on the battlefield. Political parties and various factions began to form which threatened the very existence of the fragile nation. And it appeared that Jefferson was the de facto, but completely behind-the-scenes, leader of the Republicans, whereas Adams, despite constantly denouncing parties, was leader of the Federalists because of his office.

But months before Adams’ inauguration, Jefferson, who lost to Adams in the 1796 Election, had a change of heart. He wrote a magnanimous and heart warmed congratulatory letter to his opponent and now boss.

I leave to others the sublime delights of riding in the storm, better pleased with sound sleep and a warm birth below, with the society of neighbors, friends and fellow laborers of the earth, than of spies and sycophants. No one then will congratulate you with purer disinterestedness than myself. The share indeed which I may have had in the late vote, I shall still value highly, as an evidence of the share I have in the esteem of my fellow citizens. But while, in this point of view, a few votes less would be little sensible, the difference in the effect of a few more would be very sensible and oppressive to me I have no ambition to govern men. It is a painful and thankless office. Since the day too on which you signed the treaty of Paris our horizon was never so overcast. I devoutly wish you may be able to shun for us this war by which our agriculture, commerce and credit will be destroyed. If you are, the glory will be all your own; and that your administration may be filled with glory and happiness to yourself and advantage to us is the sincere wish of one who tho’, in the course of our voyage thro’ life, various little incidents have happened or been contrived to separate us, retains still for you the solid esteem of the moments when we were working for our independance, and sentiments of respect and affectionate attachment.

As he was about to send the letter to Adams, he decided to pass it along first to his Republican protégé and master of the House of Representatives, James Madison. Madison, however, was completely baffled. Madison argued that friendship and politics were two facets of life that needed to remain separate. He concluded, as summarized by Adams biographer David McCullough, “were Adams to prove a failure as President, such compliments and confidence in him as Jefferson had put in writing could prove politically embarrassing.” In the end, Jefferson never sent the letter. McCullough lamented: “For Adams it could have been one of the most important letters he ever received. Jefferson’s praise, his implicit confidence in him, his rededication to their old friendship would have meant the world to Adams, and never more than now, affecting his entire outlook and possibly with consequent effect on the course of events to follow.” Indeed, throughout Adams’ entire presidency, it seemed as if Jefferson receded completely out of the limelight, biding his time until the Election of 1800. He did everything in his power to distance himself from Adams’ policies and even completely undermined him on numerous occasions. And it would be many more years after the election before Adams and Jefferson would even consider making contact with one another.

***

I’ve noticed throughout my life that every now and then I am in such a state to write an email that is primarily motivated by annoyance and/or anger. Telling someone exactly how you feel, explaining yourself in painstaking detail, or even laying into someone feels like such a relief when you’re fired up with those angry passions. You feel better about yourself, as if you now have a burden off of your shoulders. But once you hit the send button there is no turning back. You reread what you sent several hours or even days later and you feel embarrassed. You can’t believe how you let yourself get so carried away. You realize you sound like a whiny idiot.

***

Both of these letters/emails were motivated out of emotion and were guarded by degrees of consideration. The first was motivated out of the feeling of friendship, but was completely guarded by considerations of politics. The second was motivated out of anger, but was not guarded at all. It is curious that the former, if sent, would have made all the difference to the world to the recipient and would have repaired and improved the relationship between the two men. The latter, however, if not sent, would have spared both sender and recipient from feelings of embarrassment and awkwardness. The motivations and guardedness were completely misaligned.

The lesson I’ve learned from such experiences is that, as a rule of thumb, if you have something nice to say to someone, but are worried that it may not necessarily be politically appropriate, send it anyway. Even if you send it to someone else to review, take their advice with a grain of salt. Madison, for instance, could not have understood the deep friendship that Jefferson had with Adams. Nor could he have understood as well as Jefferson that the vain Adams would have greatly appreciated words from a man that he admired immensely. In all, the recipient will appreciate your thoughtfulness and admire your magnanimity. I’ve never regretted sending an email of kind words.

On the other hand, when you’re all fired up for whatever reason and feel compelled to fire off a nasty-gram (as they’re called in workplace), type it out, save it as a draft, and then sleep on it. When you wake up and read the email you typed out, you’ll almost always delete it and save yourself from embarrassment.

Comments on this entry are closed.

{ 1 trackback }