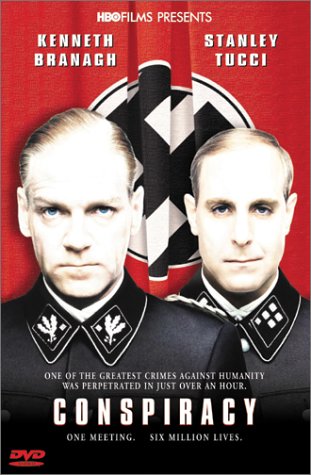

(Conspiracy movie poster. Source: Wikipedia)

(Conspiracy movie poster. Source: Wikipedia)

The 2001 film, Conspiracy, is a particularly brilliant and disturbing film about the Wannsee Conference, which was a meeting of top Nazi officials to determine the fate of millions of Jewish peoples throughout Europe during the Second World War. In a sense, the decisions made at the conference were the true beginning of the Holocaust.

The dialogue throughout the film is truly fantastic, but there is one scene, toward the end, that is remarkably striking. Reinhard Heydrich, the SS Chief of Security, played with a sinister flawlessness by Kenneth Branagh, relays a story that he was told by Dr. Wilhelm Kritzinger, deputy head of the Reich Chancellery, who while not opposed to the persecution of the Jewish peoples was bitterly opposed to their wholesale murder.

He told the story of a boy who grew up hating his father while completely devoted to his mother. Despite the protests and protection of the boy’s mother, his father would constantly beat him. Throughout his entire childhood his father was cruel and violent toward him and he ended up harboring such an intense hatred of the man his entire life. Then when the boy was now a grown man in his 30s his mother suddenly dies. What was weird was that at his mother’s funeral he didn’t shed a tear. He had dearly loved his mother, who had always been like a guardian angel to him, but he couldn’t bring himself to shed one single tear. But when his father died, he sobbed uncontrollably. He was utterly inconsolable.

The man’s whole life had revolved around this hatred of his father. Heydrich explained that “when the hate lost its object, the man’s life was empty, over.” Kritzinger was trying, in vain, to forewarn Heydrich of the consequences of enacting a policy predicated upon hatred. He was trying to get Heydrich to detach himself, even if only momentarily, from his feelings of resentment toward the Jewish peoples, which were being manifested into a bureaucratic machine, devoid of any sense of morality and proportion, and realize the sheer folly and tragedy of such a political object.

Nazi Germany set the world ablaze in their unbounded quest for Lebensraum, or “living space”, and in the enactment of policies based on their burning hatred of races they found inferior.

***

The story of the man that was totally absorbed by hatred of his father is a familiar one in the Western Canon. Some of the best-known books and stories that we’ve read or heard throughout the centuries follow similar trajectories. A person is burning with an all-consuming anger and resentment – whether from actual injustice or perceived injustice (or sometimes for reasons unknown). He is subsequently motivated by the single-minded pursuit of revenge and ends up tragically affecting not only the object of his revenge, but himself and all of those around him. These stories reflect certain constancies in human affairs and offer lessons that are relevant for our times; thus a survey of a few of the most poignant can provide us with some useful instruction.

***

Shakespeare’s Othello is one of the earliest and richest stories of hatred, revenge, and tragedy. Othello, the namesake of the play, is an African Moor who is living in and committed to the Italian city of Venice, where he serves as a respected general in the Venetian Army. Othello becomes the target of one of literature’s most sinister and archetypal villains: Iago. Iago is initially mad at Othello because Othello passed by Iago for promotion to be his lieutenant and instead promoted Cassio, a younger and, in the eyes of Iago, a less worthy man

But Iago’s hate ran deeper than the missed promotion. He explained to the audience, in Act I scene 2:

I hate the Moor;

And it is thought abroad, that ‘twixt my sheets

He has done my office: I know not if ‘t be true;

But I, for mere suspicion in that kind, will do as if for surety.

In short, he suspects that Othello had slept with his wife. Throughout the play, however, there is never any proof of this or even any small inkling that strengthens Iago’s suspicion. But in any case, that creeping doubt coupled with the resentment over the promotion seal Iago’s intent to exact revenge on Othello.

The following acts and scenes are a series of devilishly cunning manipulations by Iago that turn Venice upside-down. Iago has the uncanny ability to identify the weaknesses and insecurities that are at the core of the people around him. For instance, he recognized that beneath Othello’s bravery in battle and respect earned from his military command, he was, as an immigrant and outsider, insecure with his place in the city and ultimately with his wife, Desdemona. Iago also knew of Roderigo’s undying love for Desdemona, Cassio’s lack of tolerance for alcohol, and Desdemona’s close friendship with Cassio. He played each of these people off one another and exploited their vulnerabilities to his advantage. As Shakespeare scholar Harold Bloom judged, “He is a moral pyromaniac, setting fire to all of reality.”

In the end, Cassio was demoted and severely injured, surviving an assassination attempt by Roderigo, who ended up dead in the melee, all of which was set-up by Iago. Othello, delirious and distraught at the festering thought – planted and nurtured by Iago – that his wife Desdemona was having an affair with Cassio, smothers her to death and then kills himself. And even Iago, justly, receives punishment, most probably a death sentence.

Iago’s hatred of Othello, growing first from a slight to his pride and then stewing in his suspicions of his wife’s fidelity, led to machinations of revenge that ended up tearing the very fabric of Venetian society.

***

Roger Chillingworth, the protagonist of Nathaniel Hawthorne’s The Scarlet Letter, harbors a different type of hatred than Iago. After many years of separation at a great distance from his wife, Hester, he learned that she had an affair with an unknown man and conceived an illegitimate child; she was thus forced to wear the scarlet letter ‘A’ for her sin of adultery. (To her defense, it was widely believed that he perished at sea.)

Because of his natural social awkwardness and detachment from human emotion, Chillingworth especially begrudged his wife’s misgiving. It was one slight too many – especially from a person he was bound in matrimony – in a lifetime of exclusion from society. He made it his personal mission – indeed his life mission – to find out his wife’s suitor and ruin him. As Hawthorne described him:

In a word, old Roger Chillingworth was a striking evidence of man’s faculty of transforming himself into a Devil, if he will only, for a reasonable space of time, undertake a Devil’s office. This unhappy person had effected such a transformation by devoting himself, for seven years, to the constant analysis of a heart full of torture, and deriving his enjoyment thence, and adding fuel to those fiery tortures which he analyzed and gloated over.

Eventually the reader learns that the father of Pearl, Hester’s child, is the town minister, Arthur Dimmesdale. Dimmesdale, for obvious reasons, doesn’t want his relationship with Hester to be known to anyone. But his conscience is killing him – his soul is tormented. For consolation and counseling he, ironically, turns to Chillingworth, who is posing as a doctor for the town.

After a few sessions with Dimmesdale, who is noticeably suffering in his guilt, Chillingworth eventually begins to piece together that Dimmesdale is the father. So Chillingworth, using his privilege as Dimmesdale’s doctor, begins prying into the crevices of Dimmesdale’s mind and subtly tortures him through insinuations that exacerbate his feelings of guilt. The weight of the guilt on Dimmesdale grows so heavy that he falls into deep despair and emotional turmoil. Eventually Dimmesdale desperately confesses his sins to the townspeople, but shortly thereafter dies from heart failure, certainly caused by his mental anguish.

Chillingworth’s hatred of Dimmesdale is certainly from a legitimate feeling of injustice. Dimmesdale had an affair with his wife and they produced a child together. But Chillingworth’s single-minded dedication to revenge not only deteriorates, collapses, and kills Dimmesdale, it tears apart two people who genuinely love one another, and spoils a potential healthy family. And like the man in the first story, Chillingworth, with his perverse life mission accomplished, has nothing else to live for and dies himself as a bitter and miserable man.

***

Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick is the quintessential American novel on the destructive effects of a monomaniacal obsession. Ahab is the captain of a whaling ship who is, unbeknownst to the crew, relentlessly in pursuit, at all costs, of a white whale named Moby Dick. The crew sailed out thinking that they were searching for whales for the oil industry. But, as Melville explained, “Had any one of his acquaintances on shore but half dreamed of what was lurking in him [Ahab] then, how soon would their aghast and righteous souls have wrenched the ship from such a fiendish man! They were bent on profitable cruises, the profit to be counted down in dollars from the mint. He was intent on an audacious, immitigable, and supernatural revenge.”

Years before the story begins, Ahab encountered Moby Dick on a whaling expedition off the coast of South America. Even though Ahab successfully harpooned Moby Dick, the whale attacked the boat in retaliation and ended up biting off Ahab’s leg. With Moby Dick free, the ship made its way back thousands of miles to Massachusetts. Without any anesthetics, Ahab was in excruciating pain the entire journey home. And it was in the journey home where Ahab, with nothing to do but wallow in his own misery, began stewing for revenge against the whale that tore off his leg. Melville propounded the process of hatred that corrupted the captain: “Small reason was there to doubt, then, that ever since that almost fatal encounter, Ahab had cherished a wild vindictiveness against the whale, all the more fell for that in his frantic morbidness he at last came to identify with him, not only all his bodily woes, but all his intellectual and spiritual exasperations.”

As Melville explained, to Ahab Moby Dick was not just a wild animal that, in its impersonal nature, resisted and fought his captors and bit off one of his limbs; no, he embodied everything that Ahab found malicious in the world. “All evil, to crazy Ahad, were visibly personified, and made practically assailable in Moby Dick.”

Ever since that experience, Ahab was hell-bent on revenge. It was all he thought about – it was his burning motivation. “Ah, God! What trances of torments does that man endure who is consumed with one unachieved revengeful desire. He sleeps with clenched hands; and wakes with his own bloody nails in his palms.” Ahab even dreamt about killing Moby Dick!

But in his blind quest for revenge, Ahab put the lives of his entire crew – a dozen or so men – at risk. He didn’t care. We even learn that Ahab had a wife and young child back in America, but that didn’t stop him for a second. The concern for anything or anyone else was subordinate to his narcissistic obsession. Ahab wanted Moby Dick dead and didn’t care who went down with him.

The entire crew – except one – perished because of Ahab’s monomania. Ahab harpooned Moby Dick again, but instead of losing a leg, this time he lost his life.

***

These stories – of hatred, obsession, revenge, and tragedy – are all familiar to us. Their familiarity reveals not only something constant in human nature but also aspects of our own culture.

As human beings, we’ve all felt that we’ve been wronged, slighted, or even betrayed; likewise there are people out there who feel that we have done the same to them. And we all have imagined the pleasure of sweet, sweet revenge.

But what is at the root of such hatreds? And why are some people – at least those in these stories – more predisposed to such intense emotions? The philosopher-cum-dock worker Eric Hoffer asked, then answered: “Whence come these unreasonable hatreds, and why their unifying effect? They are an expression of a desperate effort to suppress an awareness of our inadequacy, worthlessness, guilt and other shortcomings of the self. Self-contempt is here transmuted into hatred of others – and there is a most determined and persistent effort to mask this switch.” To Hoffer, hatred begins from within. At its root is a perception that something is lacking or missing or not good enough in our own lives. And it is outwardly channeled onto other people or objects. Once these feelings are transmuted onto something else, we no longer need to take responsibility for our actions (or lack thereof). Now we are longer to blame for our own problems or shortcomings; now someone else is to blame. And it is much easier and pleasant to blame someone else than to take a brutally honest introspective look at ourselves in the mirror and identify what’s wrong in our own lives. Once the father of the man in the first story died, he realized that aside from spending his time stewing about his abusive father, he had lived an empty life.

As illustrated in the stories above, the burden of a grudge is heavy on the human heart. It is perverse, corrupting, and dangerous. All antagonists, in their desperate quests for revenge, ended up killing people and themselves as well. They exited a world that was ablaze from the kindling of their insecurities.

One of the principal teachings of the Bible, integral to our Judeo-Christian Western culture, is of forgiveness. Psalms 86:5 says “For thou, Lord, art good, and ready to forgive; and plenteous in mercy unto all them that call upon thee.” To forgive and forget is a sign of personal strength and wisdom; festering hatred and the pursuit of revenge, however, is a sign of weakness and insecurity. The quicker we let go of a slight to our person, the quicker we can move on and live our lives to the fullest without getting bogged down in trivialities.

Comments on this entry are closed.