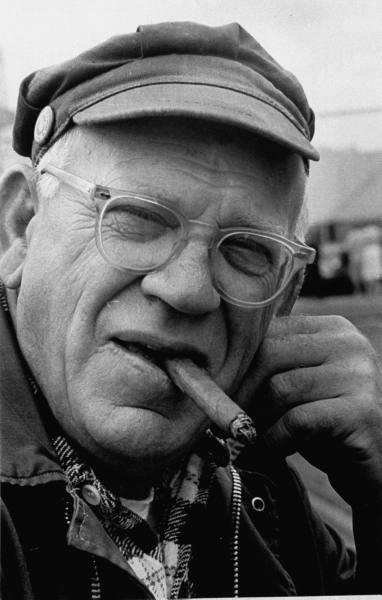

This week marks the 30th Anniversary of the death of Eric Hoffer, a rare gem in American philosophy largely forgotten today.

Hoffer’s thoughts and analyses, elucidated mostly in short essays, penetrate the deepest recesses of the human soul and spirit. His only book, The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements, was widely read throughout the Cold War, most famously by Presidents Eisenhower and Kennedy. That book, just as relevant and provocative today, provides rich commentary on the psychological underpinnings of the mass movements that shaped much of the 20th Century. While Hoffer is best known for his insights on power and human nature, his commentary on the American middle class, as well as his life’s example, are inspiring and instructive for a 21st Century audience.

Born the son of a Bronx cabinetmaker, Hoffer spent most of his adolescence blind. Miraculously regaining his sight as a teenager, he eventually decided upon two things. First, he would educate himself by devouring any and every book he could get his hands on. He became a deeply read student of the Great Books. His favorites, however, were French writers such as Alexis de Tocqueville, Blaise Pascal, and especially Michel Montaigne. He felt as though Montaigne was writing for him. “He knew my innermost thoughts.” It was Montaigne who “gave me a taste of a good sentence.” And second, he would earn a living in manual labor, working as anything from a migrant fruit picker to a gold miner to a lumberjack, eventually settling as a San Francisco dockworker.

It was his Socratic devotion to that second principle that separates him from scholars of his day and ours. “I’m a common man, and proud of my commonness,” he once said. “But talent is common too.” It was only by working among average Americans, he added, could he fully observe and appreciate the American working and middle classes, which are “lumpy with talent”.

It’s easy to take for granted, but much of the specialness of America is that people of any race, religion, and even of any social or economic standing can thrive and prosper here. “Only in America” Hoffer wrote, “were the common folk of the Old World given a chance to show what they could do on their own, without a master to push and order them about.” Without an aristocratic or autocratic ruling class breathing down their necks, the common people were free to choose their own destiny and reach their full human potential. In America, they “find here their natural habitat, their ideal milieu, which brings their energies and capacities into full play.”

But what is it about America that makes it possible for the average person to achieve greatness? Hoffer turns to the middle class. “The middle class is the least elitist ruling class we know of. Not only is it wide open to all comers, but it aspires to a state of affairs in which things happen of themselves, and regulate themselves. Unlike any other ruling class, the middle class has found it convenient to operate on the assumption that if you leave people alone they will perform tolerably well.” If left alone, without the minutiae of everyday life burdened by restrictions or regulations, the average American is free to take risks and to experiment and tinker.

For instance, the Space Race, one of America’s proudest claims to greatness, was led by average Americans from small towns. These men were free to risk their lives as test pilots and then as astronauts. Reflecting on this phenomenon, Hoffer wrote “It tickled me no end that the astronauts who landed on the moon were not elite-conscious intellectuals but lowbrow ordinary Americans. It has been the genius of common Americans to achieve the momentous in an unmomentous matter-of-fact way.”

And even the freedom of the average American to tinker around in a garage, basement, or dorm room is a source of America’s greatness. “All through the ages man’s inventiveness was greatest when he played and tinkered with things at leisure and to no useful purpose.” Adding, “The beauty of it is that eventually, man’s playful purposeless tinkering resulted in useful devices.” The genesis of Microsoft, Apple, Dell, and Facebook can all be traced to average Americans tinkering around with their computers in their free time.

Eric Hoffer and his work are timeless. His insights are just as relevant today as they were when he penned them. Reading his work today is like reading a field guide to contemporary politics. Remembering his life, however, is to reflect upon this self-described common man and how he realized his potential as one of the greatest American thinkers of the 20th Century.

Comments on this entry are closed.