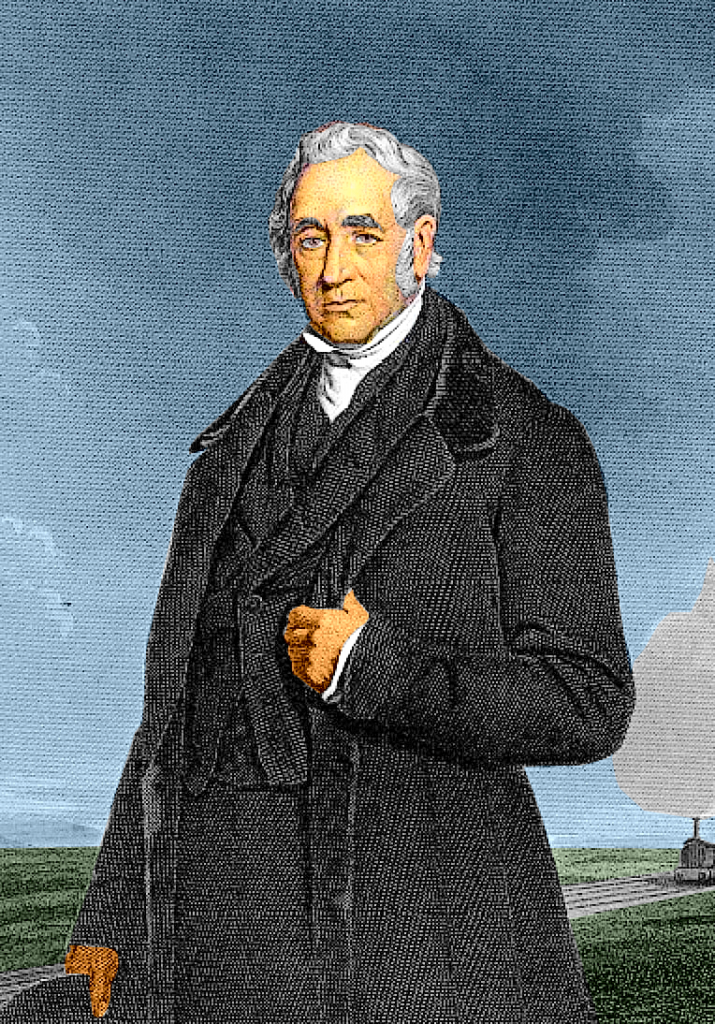

(George Stephenson. Source: Wikipedia)

(George Stephenson. Source: Wikipedia)

At the age of 18, George Stephenson (1781-1848), later known as the “Father of Railways”, had no formal education. In fact, he could neither read nor write. Coming from the northeastern coal-country of England, he was not only unschooled, but also penniless and without any sort of family connections with which to launch a promising career.

But Stephenson was not without knowledge. By the beginning of his adulthood, he had been, as Paul Johnson writes in his Birth of the Modern, “a herdsman and a welder, had driven a gin horse, and had served as an assistant fireman, fireman, then engineer – mending shoes and clocks in his spare time; the year before he had been put in charge of a giant new pumping engine at a major pit, consulting with the man who designed it, a brilliant designer called Robert Hawthrone.” Despite a lack of proper education, Stephenson had by all measures a deep and practical learning in the mechanical arts.

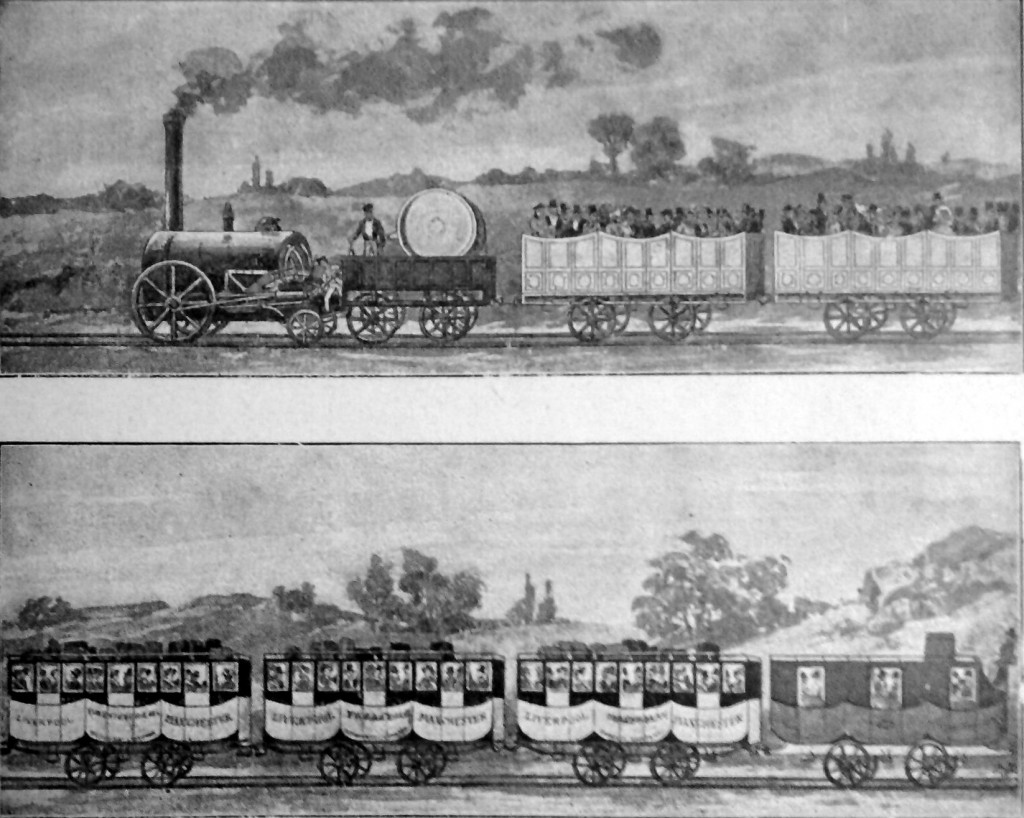

(Picture of the first passenger locomotive line, the Liverpool & Manchester Railway. Source: Wikipedia)

(Picture of the first passenger locomotive line, the Liverpool & Manchester Railway. Source: Wikipedia)

Stephenson, who went on to build history’s first public railway line, acquired an education not from inside a classroom but instead from hands-on experience tinkering with machines and gadgets as well as working various jobs throughout his boyhood. His smattering of jobs gave him a deep familiarity with all sorts of tools and mechanical devices, becoming incredibly proficient around a workshop. Quickly mastering one task after another, he worked his way up to become an engineer, becoming intimately acquainted with the mechanisms of steam-engine technology, the pioneer use of which was catalyzed by James Watt about two decades prior.

By the mere age of 18, Stephenson was an expert engineer and mechanic. He had early exposure to steam-engine technology and, though not the inventor of the locomotive, made its widespread adoption both feasible and practical. The locomotive went on to revolutionize the world in the 19th Century and beyond, first as a coal transport and then as a much improved alternative to horse carriages.

***

Steve Jobs was a similar type of tinkerer. Brought up by adoptive middle class parents without any particular connections, he too had very little formal education (a semester at Reed College). Despite such circumstances, he learned his craft through experience, tinkering with early computers and electronics in various jobs and in his free time.

Jobs’ early exposure to electronic technology was through his father. As a machinist for a company that developed lasers, Jobs’ father taught him the basics of electronics. In a 1985 interview with Playboy, Jobs said that his father was “a sort of genius with his hands… [and] used to get me things I could take apart and put back together.” Through patience and practice, Steve acquired his father’s steady and trained hand to gracefully maneuver around a circuit board.

His first real introduction to a full-fledged computer was when he was 12 years old. One of Jobs’ neighbors at the time was an engineer for Hewlett-Packard. He would invite kids from throughout the neighborhood over to his place and allow them to play around with his personal computer. His neighbor spent a lot of time with Jobs and taught him the basics on one of the first computers. From that point on, Jobs was hooked. He then, as he recalled in the interview, “wanted to build something and I needed some parts, so I picked up the phone and called Bill Hewlett—he was listed in the Palo Alto phone book. He answered the phone and he was real nice. He chatted with me for, like, 20 minutes. He didn’t know me at all, but he ended up giving me some parts and he got me a job that summer working at Hewlett-Packard on the line, assembling frequency counters… I was in heaven.” Jobs was now being paid to tinker.

After dropping out of Reed, Jobs went back to his hometown and garnered a position at Atari, working on a project to develop a basketball game to follow-up the success of Pong. When that project fell through, he traveled around Europe for Atari for some time, fixing various engineering defects in their products. After a short leave of absence, he came back to Atari, though grudgingly, and also started attending Homebrew Computer Club meetings with his friend Steve Wozniak. The meetings of the club revolved around a computer kit called Altair, which allowed people to build their own personal computer. After he and Wozniak spent much time tinkering around with the Altair, they decided that they could make a better computer and thus formed Apple.

***

Neither Stephenson nor Jobs received formal educations in mechanical engineering or computer science. Neither received accreditations from trade guilds or professional associations. Nor did they invent the locomotive or the personal computer, respectively.

What they did was spend their time learning about something that fascinated them, something that irreversibly fastened its hooks into their imagination. From that point on, they spent their free time, from young boys to grown men, tinkering around with machines and computers, taking them apart and putting them back together, intimately studying how they worked. They experienced that frustrated pleasure that only tinkerers feel when spending hours trying to figure out why something doesn’t work only to find out that it was something so laughably minor that caused such distress. Then they took jobs – probably at little pay – where they could be in a workshop where they could tinker with tools and technology that they couldn’t afford. The aggregation of these experiences tinkering around ultimately created a person who was deeply familiar with an existing technology, understood its limitations yet grasped its practical potential, and improved upon its design, catalyzing a revolution in innovation.

***

Innovation, it is almost universally agreed, has been one of the biggest factors in the success of the United States. Our nation’s ability to churn out people like Steve Jobs, John D. Rockefeller, Andrew Carnegie, Bill Gates, the Wright Brothers, and Henry Ford is what has given us a standard of living never before reached in the history of mankind. And it is therefore essential, if we are to retain our place as the most attractive country to live in the world, that we ensure our edge in the development of innovators.

Indeed, in his 2011 State of the Union Address, President Obama said “The first step to winning the future is encouraging American innovation.” Republican presidential hopeful, Mitt Romney, in a speech to the employees of Microsoft also stressed the importance of innovation if the 21st Century is to be the next “century of America.” Listen to any politician speak of the economy and technological innovation is almost always mentioned.

But as we contemplate how exactly we create an environment and culture conducive to innovation, we should not forget how tinkerers like George Stephenson and Steve Jobs came about.

Comments on this entry are closed.